In early 2018 I acquired a collection of American newspapers from the 1930s and early 1940s. In stark fashion all share an article about Hitler’s Germany. I was particularly struck by how the archive reflects an unfolding of events in a “daily” context—a harbinger of the imminent Holocaust. Returning to that era’s quotidian from the vantage point of our own has been especially potent and unsettling. For this project, ten to twenty original newspaper pages are framed; placed between each is a black and white photographic image culled from my own previously unprinted proofsheets from the 1980s and early 1990s—observational in nature, documenting moments from everyday life—a dead possum, the shadow of a swing on sand, a group of people gazing upward at a subject off-frame, a church marquee with the words “DISTANT FROM GOD.”

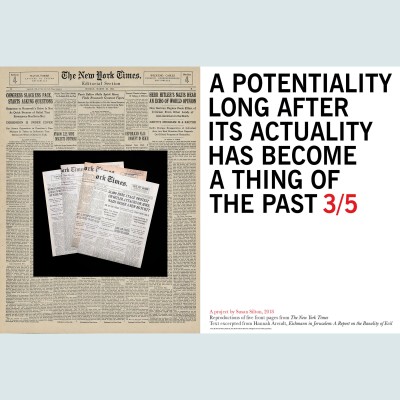

A potentiality… exists in various forms: the exhibited form as described above, and a mailed version pictured here, which consists of digital reprints of five New York Times front pages from the early 1930s. Over the course of several weeks beginning in January, 2019, I mailed the set of prints to a list that included artists, political journalists, and leaders at the forefront of civil rights advocacy in the US. Echoing the steady march towards an eventual Holocaust, the mailings—sent one at a time every couple of weeks—reflected the accumulative weight of witnessing.

This work insists on the importance of remembering the mundane across multiple generations, on the vital role of a free press in disseminating truth, and on the certainty that malevolent forces working against progress, criminal justice reform, and democracy are never limited to rising just in the past. History always has the potential of repeating. The title of the work is excerpted from political theorist Hannah Arendt’s iconic 1963 text, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Arendt fled Germany during Hitler’s rise to power, and reported on Adolf Eichmann’s infamous trial for The New Yorker.

"But I think it is safe to predict that this last of the Successor trials will no more, and perhaps even less than its predecessors, serve as a valid precedent for future trials of such crimes. This might be of little import in view of the fact that its main purpose - to prosecute and to defend, to judge and to punish Adolf Eichmann - was achieved, if it were not for the rather uncomfortable but hardly deniable possibility that similar crimes may be committed in the future. The reasons for this sinister potentiality are general as well as particular. It is in the very nature of things human that every act that has once made its appearance and has been recorded in the history of mankind stays with mankind as a potentiality long after its actuality has become a thing of the past. No punishment has ever possessed enough power of deterrence to prevent the commission of crimes. On the contrary, whatever the punishment, once a specific crime has appeared for the first time, its reappearance is more likely than its initial emergence could ever have been.”